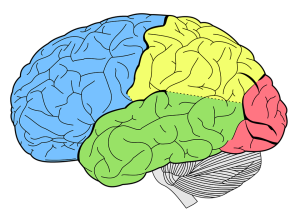

As a clinician who works with patients who experience chronic pain and who recognizes the importance of this topic, I take great pride blogging about the fact that September is Pain Awareness Month. More than fifty percent of individuals who experience chronic pain also develop depression. In fact, both chronic pain and depression activate the same areas in the brain.

Not all pains are created equal. In fact, there are many different types of pain. Chronic pain is subdivided into nociceptive pain, which is pain caused by inflammation or damaged tissue, and neuropathic pain, which is nerve related pain.

Nociceptive pain can be further divided into superficial and deep pain. The superficial pain pathway is stimulated is by nociceptors (sensory pain receptors) in the skin or superficial tissues. Deep pain is further subdivided into somatic and visceral pain. Deep somatic pain is felt when nociceptors in ligaments, tendons, bones, blood vessels, fascia, and muscles are stimulated. It is often described as dull, aching, and poorly-localized pain. Deep visceral pain, on the other hand, originates in the organs. While the location of visceral pain may at times be easy to identify, it is often extremely difficult to pinpoint its location.

As opposed to nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain is divided into peripheral and central pain. Peripheral pain originates in the peripheral nervous system (the portion of the nervous system that exists outside of the brain and spinal cord), and it is often described as burning, tingling, stabbing, or pins and needles. Central pain is pain that originates in the brain or spinal cord.

Pain breeds pain. What this means is that as an individual chronically experiences pain, the threshold decreases for pain signals to be transmitted via C-fibers to the brain. In other words, the same signal that previously would be perceived as non-noxious (non-painful) will be perceived as painful. The cortical somatotropic organization of the brain is different than previously in this case of neuroplasticity gone awry. This is referred to as the pain wind up phenomenon or central sensitization. In fact, MRI studies have revealed that pain processing centers of the brain appear different, including abnormal grey matter loss (especially in the prefrontal cortex and right thalamus) in individuals experiencing chronic pain compared to individuals who do not. These brain changes are reversible if the state of chronic pain is terminated.

For those who are curious to learn more about pain and how it affects the brain, I refer you to Explain Pain, by David S. Butler and G. Lorimer Moseley. This book, which is appropriate for clinicians and patient alike, explains what occurs when an individual experiences pain and explores pathways to resolve pain.