On Tuesday, April 16, The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) officially forced the two remaining companies that sell medical mesh for transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair surgeries, Boston Scientific and Coloplast, to discontinue all sales in the United States. This bold and powerful move is one that many pelvic floor therapists have been long awaiting. For years, we have witnessed the deleterious effects that mesh has on our patients, and we have seen the extent of the damage it can cause. Finally, the FDA has gotten the memo, and they are prohibiting doctors from further usage of this product. Pelvic floor therapists around the world are breathing a sigh of relief and saying, “It’s about time.”

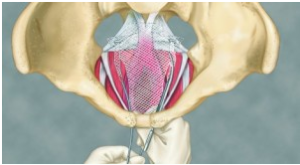

But let’s rewind a bit and provide some historical background. Gynecologists have been utilizing mesh since the 1970s to correct pelvic organ prolapse, also known as descent of one (or more) of the pelvic organs (bladder, uterus, and/or rectum). When the suspensory ligaments that attach to the organs or the supportive muscles beneath the organs weaken, the organs may descend lower than they should. Mesh is a device that provides additional support to the weakened tissue. Surgical mesh is typically comprised of either synthetic material or animal tissue. Mesh repair surgeries have been performed transabdominally as well as transvaginally. Both approaches have been deemed “controversial” in the past decade, especially after complaints began pouring in by the dozen. In fact, the 2016, the FDA acknowledged increasing concern by changing the former classification of transvaginal POP mesh from a “moderate-risk device” to a “high-risk device.” However, it wasn’t until last month that the product was recalled altogether…for treatment of POP.

But…mesh has also been used to treat stress urinary incontinence. It has been implanted transvaginally to support the bladder neck or urethra (also referred to as sling procedures). And yet, the FDA has NOT banned usage of mesh for these procedures because…your guess is as good as mine.

According to the FDA, approximately 10-15% of the 10 million women worldwide who have undergone these surgeries have experienced serious complications. Within the United States, more than 10,000 reported complaints of severe injury and eighty deaths as of last year. More than 100,000 people have filed complaints against mesh manufacturers at both the state and federal levels.

These statistics include both prolapse repair and urinary incontinence related surgeries. Shockingly, the FDA has only recalled mesh within the context of prolapse related surgeries. How many more women who have undergone sling surgeries will need to suffer before the FDA gets another wake up call? How many more reports will need to be filed?

Please allow me to be clear- my goal is NOT to frighten women who have undergone successful mesh repairs. If you have had a surgery involving mesh and are feeling better, mazal tov! I am thrilled to hear that, and I hope you continue to feel wonderful for many happy and healthy years. My very strong opinions are being expressed from the perspective of a therapist who has worked with the minority of mesh recipients who are struggling, of the ones who have experienced complications that include pain, infection, dyspareunia (pain during intercourse), urinary complications, bleeding, and/or organ perforation. So yes, I am extremely biased. And I am also biased against surgery altogether as a pelvic floor specialist.

Why are thousands of women being operated on, undergoing invasive and often unnecessary surgical procedures, for POP and urinary incontinence, both of which can be significantly improved with conservative pelvic floor physical therapy? Kate Haranis, a spokeswoman for Boston Scientific, foolishly stated that “the inaccessibility of these products will severely limit treatment options for the 50 percent of women in the U.S. who will suffer from pelvic organ prolapse during their lives.” (Oh yeah, by the way, she also admitted that transvaginal mesh accounts for $25 million in annual sales for the company.) I counter that the inaccessibility of these products will prevent further harm to suffering women who are given misinformation by their doctors. I also would wager money on the fact that Haranis has not done her homework on the benefits of pelvic floor physical therapy. She is not aware that studies have revealed that on average, pelvic floor physical therapy has been shown to reduce prolapse by one grade (out of four). I wonder if she has ever even heard of a pessary, another alternative to surgery.

Ladies, granted, we have won a big battle, but we are still fighting a war. The road ahead of us may be long and arduous, but we won’t quit. We pelvic floor physical therapists will continue to fight alongside you, and we will educate as many medical practitioners as possible about the benefits of pelvic floor physical therapy as the first line of defense against POP and incontinence.